For decades the U.S. Has relied on spy satellites to look deep inside the territory of its adversaries. These giant billion-dollar satellites take high resolution photographs which can see objects as small as a fist inside Russia, North Korea or wherever the target is. Tonight we will take you inside the intelligence agency where those photos are analyzed, and we will also take you inside a revolution that is rocking the top secret world of spy satellites. A private company named Planet Labs has put about 300 small satellites into space, enough to take a picture of the entire land mass of the Earth every day. Those small satellites have created a big data problem for the government which can't possibly hire enough analysts to look at all those pictures. Welcome to the revolution.

This is how the revolution began. Twenty-eight small satellites sent out into orbit by astronauts from the biggest of all satellites, the International Space Station.

Robbie Schingler: We took a satellite that would be the size of a pick-up truck and we shrunk it. We wanted to make it about the size of a loaf of bread.

Robbie Schingler began building satellites 20 years ago, working for NASA.

Robbie Schingler: The way that I grew up-- at NASA is we would spend about five to ten years, even-- to build one satellite.

Now he's one of the founders of Planet Labs.

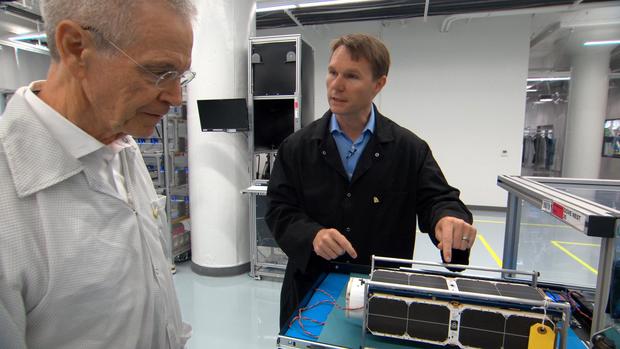

Robbie Schingler: This is our satellite manufacturing building

A company that turns out satellites in months not years.

Robbie Schingler: You can pick these up. They're about 12 pounds or five kilograms.

Packed with some of the same electronics used in smartphones, they're built by hand in a nondescript building in downtown San Francisco.

Robbie Schingler: It looks like a warehouse and our engineers here build and operate the largest fleet of satellites in human history.

David Martin: That's a pretty big statement: "largest fleet of satellites in human history."

Robbie Schingler: I know. Isn't that cool? And frankly we're just getting started.

David Martin: How many have you built over the years?

Robbie Schingler: Oh, over the years, we've built about 300 satellites. Over the years. And last year we launched about 146 satellites into space.

The satellites are called doves. Here on the production floor they are kept in "nests," waiting to be launched in "flocks."

Robbie Schingler: This is a visualization that shows every satellite that we have up in space today.

David Martin: This is mission control?

Robbie Schingler: This is mission control, yeah.

David Martin: It's a little bit of a letdown.

Robbie Schingler: It's a little bit non-traditional. A-- a normal mission control you will have dozens and dozens of engineers for one satellite. We flip that around, so we have dozens of satellites for a single engineer.

The satellites orbit the globe every 90 minutes while the Earth rotates beneath them, their cameras documenting the planet as it's changing.

Will Marshall: I'm always astonished that almost every picture we get down, we compare it to the picture from yesterday, and something's changed.

Will Marshall is another of the company's founders.

Will Marshall: We see rivers move, we see trees go down, we see vehicles move, we see road surfaces change and it gives you a perspective of the planet as a dynamic and evolving thing that we need to take care of.

David Martin: Is that what people are supposed to conclude from seeing all this change?

Will Marshall: Well, you can't fix what you can't see.

That kind of save-the-world ambition carries a big risk, especially for a small firm that's just getting started.

Will Marshall: Planet has many records. We've launched the most satellites in the world ever, but we've also lost the most satellites ever.

Four years ago, Marshall gathered his staff in what planet calls the "mothership" to watch a rocket carrying 26 doves blast off.

Will Marshall: It was a big deal. And we had a customer in the audience at the time that we had brought to see a launch. It was really embarrassing.

Chester Gillmore: I'll never forget it we see the, you know, smoke coming and everyone's cheering and then it goes, and then ka-boom.

Chester Gillmore runs Planet's satellite assembly line.

David Martin: You lost how many satellites?

Chester Gillmore: Twenty-six, I think we lost, yeah, 26 (makes explosion sound).

David Martin: Those are your babies.

Chester Gillmore: They were. That was a tough, yeah, they were.

David Martin: How long did it take to get back to normal?

Chester Gillmore: We didn't even skip a beat when that happened, didn't lose a day.

On the day we visited Planet its satellites were beaming down 1.2 million pictures every 24 hours.

Planet sells images to over 200 customers, many of them agricultural companies monitoring the health of crops. But this is Planet's most important customer.

Robert Cardillo: So, this is our operations center. Heartbeat of the agency.

Robert Cardillo is director of the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, NGA for short, the organization which analyzes satellite photos.

David Martin: So this really is ground zero for all the intelligence coming in from space?

Robert Cardillo: That's correct. It's-- it's where we bring in all of our sources, whether they come from space or any source. But, correct, it's ground zero.

Because 60 Minutes was allowed into this secure operations center, top-secret high-resolution pictures taken by spy satellites are nowhere in sight.

Robert Cardillo: Across the center. You see one of the outposts that the Chinese have developed in the South China Sea.

Cardillo says lower resolution images like this one are taken by commercial satellite companies are changing his world by giving him more and more looks at the Earth, especially places U.S. spy satellites are not zeroed in on.

Robert Cardillo: I'm quite excited about capabilities such as what Planet's putting up in space.

Planet is a small company with just over 400 employees, many of them in San Francisco. NGA is a government bureaucracy with a workforce of 14,500 and a 2.7 million square-foot headquarters south of Washington D.C. But Robert Cardillo knew a revolution when he saw one.

Will Marshall: This is not a scale model. This is the real size.

When Planet's Will Marshall unveiled his small satellite at a 2014 Ted Talk, Cardillo showed the video to his work force.

Will Marshall: It's going to provide a completely radical new data set about our changing planet.

And a radical new culture. Planet openly markets its images. NGA's spy photos rarely see the light of day. The intelligence analyst who leaked these photos of a Russan shipyard in 1984 went to prison. What NGA can see from space is top secret.

David Martin: How many of these high resolution satellites do you operate?

Robert Cardillo: I'll not comment.

But much of what Cardillo won't talk about is common knowledge to Ted Molczan, who is a household name in the obscure world of amateur satellite tracking.

David Martin: How many photo satellites does the U.S. have in orbit?

Ted Molczan: Currently there are three.

Since we interviewed Molczan, what looks like a fourth photo satellite has been launched. He tracks them from his balcony in downtown Toronto with nothing more sophisticated than $300 binoculars.

David Martin: You just wait for a fly-by...

Ted Molczan: Yeah.

David Martin: ...from a satellite.

Ted Molczan: Yeah. I'm laying in wait.

David Martin: For something that's 150 miles away going five miles a second.

Ted Molczan: Yes. And it will cross my field of view in a few seconds. So I've gotta be on the ball.

Here's what a top secret satellite looks like from Earth, captured on video by one of about 20 amateur trackers around the world.

Ted Molczan: Its code name is Crystal. This thing is about the size of a city bus.

David Martin: And this is what it looks like from Earth?

Ted Molczan: That's right. It just looks like a moving star.

The satellite trackers watch as it streaks across the sky, measuring its position against well-known stars.

David Martin: That's enough to tell the orbit of the satellite?

Ted Molczan: Yes. We're doing this with our eyes, often with cameras, but the end result of it is numbers. And if we pool enough of that data together, we can actually calculate the orbit to great precision.

David Martin: If you've been able to calculate this, presumably the North Koreans have been able to calculate this.

Ted Molczan: Absolutely, yes.

David Martin: So there's no mystery to the North Koreans, the Russians, the Iranians, the Chinese when these satellites are overhead taking pictures?

Ted Molczan: That's right.

It's space-age hide and seek. Adversaries know when and where American spy satellites are looking but can never be sure what they're finding.

Robert Cardillo: This is what NGA developed in the pursuit of Osama bin Laden.

Before President Obama and his national security team, including Cardillo there on the left, gathered in the White House Situation Room on the night of the raid, NGA had gone back in time through seven years of satellite imagery to construct this scale model of Bin Laden's hideout.

Robert Cardillo: We had historic imagery of this compound that enabled us to reverse time.

NGA could see not just the outside, but inside as well.

Robert Cardillo: It enabled us to go back to the point of construction. And essentially through our imagery archive to rebuild the house so, we could see how the first floor was designed and how the rooms would lay out, where are the stairs from the first to the second floor and the second to the third floor.

David Martin: So old pictures show that building before the roof went on?

Robert Cardillo: We had pictures before the compound existed. We saw it when it was first constructed and as it, as it was built over time. Correct.

David Martin: And that's how you could find out the dimensions of each room?

Robert Cardillo: Indeed.

The satellites that made that possible are the equivalent of a Hubble Space Telescope. But instead of taking pictures of the heavens they are zeroed in on Earth, able to make out objects just four inches across.

For decades they have been indispensable to knowing what America's adversaries are up to, but like Hubble they cost billions of dollars each. Which is one reason there are so few in orbit.

David Martin: Are they putting more up?

Ted Molczan: They've never had more than four up at a time.

Which is why Cardillo is so interested in Planet and its small satellites that deliver a tsunami of data like NGA has never seen.

David Martin: How many analysts would it take to keep up with those number of satellites?

Robert Cardillo: We did some calculations and we came up with six million humans would need to be hired to exploit all the imagery that we have access to. You can see that it's not exactly a viable proposition.

Shawna Wolverton: If you were trying to find this in Syria, it's sort of, like, a needle in a haystack, right?

Planet's Shawna Wolverton showed us how a computer can be programed to help track the impact of Syria's Civil War on the people who live there.

Shawna Wolverton: So, what we've done is created a algorithm that looks for new roads and buildings.

An algorithm that rifled through reams of satellite photos and identified the first signs of a new refugee camp.

Shawna Wolverton: Here's that first image.

David Martin: So, that red grid is what?

Shawna Wolverton: Those are new roads. And all of these blue spots that you can see here are buildings.

David Martin: So, this is one little corner of, of Syria. Could you do this for the entire country?

Shawna Wolverton: We can absolutely do this for the entire country. I can show you over here. We can zoom out. And you can see that we've run this algorithm over the entire country and you can see all of the roads and buildings.

This is the first photo an American spy satellite ever took from space, in 1960. A far off look at a Russian airfield. Since then we have gotten much more spectacular looks at Earth, like these taken by the Apollo astronauts. But the U.S. government no longer holds a monopoly on photos from space and has no power to stamp top-secret on any of the 800 million images Planet has taken in its brief lifetime.

David Martin: Making it available to everybody, people are going to come up with uses of that imagery that you haven't...

Will Marshall: Yeah.

David Martin: ...imagined.

Will Marshall: Dreamed of, yeah.

David Martin: And not all of them are going to be good.

Will Marshall: No.

David Martin: You worry about that?

Will Marshall: I worry a lot and we wouldn't have started Planet if we didn't have a very strong conviction that the vast majority of the use cases are very, very positive.

Produced by Mary Walsh and Tadd J. Lascari

Read Again https://www.cbsnews.com/news/private-company-launches-largest-fleet-of-satellites-in-human-history-to-photograph-earth-60-minutes/Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Private company launches "largest fleet of satellites in human history" to photograph Earth - CBS News"

Post a Comment