For the past 45 years, Patagonia has been a business at the cutting edge of environmental activism, sustainable supply chains, and advocacy for public lands and the outdoors. Its mission has long been “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”

In just the last few years alone, the company has expanded its used clothing program, amped up its investment in sustainable startups, launched an activist hub to connect its customer base directly with grassroots environmental organizations, and taken the Trump administration to court over its public lands policy. And just last month, CEO Rose Marcario announced it was giving back $10 million in tax cuts to grassroots environmental organizations.

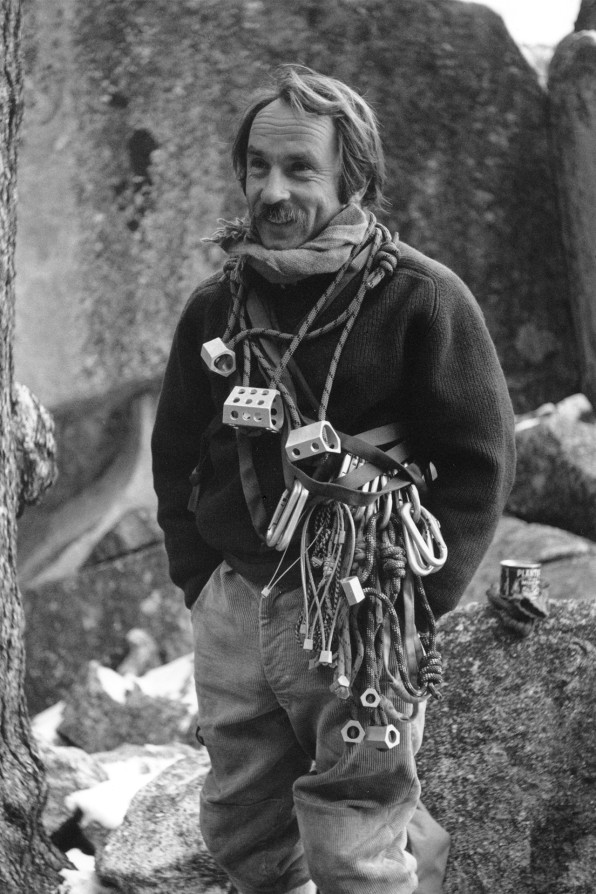

But for Yvon Chouinard, that’s not enough. So this week, the 80-year-old company founder and Marcario informed employees that the company’s mission statement has changed to something more direct, urgent, and crystal clear: “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.”

In an exclusive interview with Fast Company, Chouinard says the shift in mission may sound trivial–obviously those ubiquitous fleeces aren’t going anywhere–but it’s actually fundamental to almost every aspect of the company. The key is in its expression of urgency, to signal to everyone inside the company and out, that this isn’t just about climate change, it’s a climate crisis.

While months in the works, Patagonia’s announcement comes as major scientific reports have detailed the consequences of unchecked climate change. The Fourth National Climate Assessment by the White House released just a few weeks ago outlined the potential societal and economic impact, which includes annual losses in some economic sectors projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars by the end of the century.

Chouinard is blunt in his own assessment of the level of urgency. “This is Pearl Harbor. The whole country, and whole world, has to mobilize to do this,” he says. “It’s triage. I remember when I was a kid during World War II, we didn’t have any meat to eat. There was no beef, there was no sugar, people had to grow their own gardens. The whole country mobilized. That’s what has to happen now. So I didn’t think we were taking climate change seriously enough. We were supporting too many causes that were working on symptoms and not actual causes and solutions.”

The new mission statement impacts every single job in the company. About six months ago, Chouinard gave the HR department some new marching orders. “Whenever we have a job opening, all things being equal, hire the person who’s committed to saving the planet no matter what the job is,” he says. “And that’s made a huge difference in the people coming into the company.”

It’s also influencing who Patagonia works with as brand ambassadors–being a great surfer is cool, for example, but they also have to be committed to being strong and vocal environmental advocates–and the grassroots activist organizations it funds. “We give out about 900 grants a year to different activist organizations,” says Chouinard. “We’ve given money to an organization that repairs people’s bicycles. Well, they’re not going to get any money any more.”

To figure out the best way the company could have the most effective impact, Chouinard and Marcario had to ask themselves questions like, what are Patagonia’s resources? Where does the company have influence? And what should it be putting money into? They came up with three key answers: agriculture, politics, and protected lands.

Right now the company is working with about 100 small farmers who grow cotton regeneratively in India, which is being expanded to 450 next year. They control the pests with traps, they weed and gather the cotton by hand. “That’s what you have to do, replace all the chemicals with knowledge and labor,” says Chouinard.

And they can also sell the cover crops planted to help protect the cotton, “So they get another 10% from us for growing regeneratively, they can sell their cover crops, and they’re happy,” Chouinard says. “We’re going to be making regeneratively grown cotton stand-up shorts, not only employing people, but from a crop that actually captures carbon. That’s a win-win for everybody.”

In politics, ahead of the 2018 midterm election, Patagonia became one of the first consumer brands ever to make the endorsement of specific candidates part of its brand marketing. It posted endorsements of Nevada Democratic candidate Jacky Rosen in Nevada and incumbent Montana Senator Jon Tester on its website, across its social channels, and in customer emails. Chouinard says to expect the company to speak up more loudly and often.

“Jon Tester barely won in Montana. I’ve had people in Montana tell me he probably wouldn’t have done it if we hadn’t helped,” he says. “That makes me feel pretty good! We have this political power, a few million customers who are really behind what we’re doing. So why not use it to do some good?”

For protected lands, it goes beyond advocating and fighting for public lands, as the company has been doing for Bears Ears in Utah. Smaller, more strategic investments of money and time have the potential for significant impact. Last May, Chouinard talked to Kristine Tompkins, president of Tompkins Conservation, about an idea for creating a new park at the very tip of South America. “I’ve been there and it’s a wild, wild place,” Chouinard says. “There’s no roads, no trails, just a lot of swampland that captures a tremendous amount of carbon. So I thought it’d be a perfect place for a protected parkland.”

Patagonia gave Tompkins Conservation $185,000 to get on it. And they did, working with the governments of Chile and Argentina. After an Argentina government votes tomorrow, the hopeful result is two new national parks, covering up to 25 million acres. “It’s not like we had to buy up a ton of land and force our way in. It’s strategic investment that has really paid off,” says Chouinard. “This whole thing will be done by Christmas. Can you believe it?”

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Patagonia's new company mission is to save the planet - Fast Company"

Post a Comment