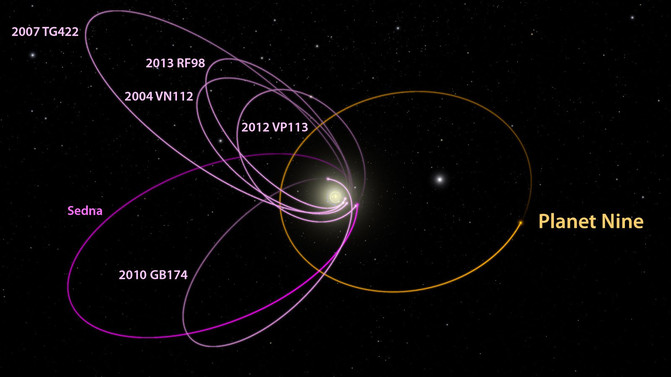

Caltech astronomers suggested in 2016 that orbits of these 6 extreme trans-Neptunian objects (in magenta) – all mysteriously aligned in one direction – might be explained by the presence of a Planet Nine (in orange) in our solar system. Despite searches, no Planet Nine has yet been found. Image via Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC).

As recently as late May, an international team of researchers presented new evidence for an unknown Planet Nine at the fringes of our solar system. The evidence came from analysis of an oddball object in the outer solar system – 2015 BP519 (aka Caju) – whose unusual orbit had been predicted by computer models used by astronomers who’ve been searching for Planet Nine since 2016. Last week, however, other astronomers – members of the Eccentric Dynamics group at University of Colorado, Boulder – presented evidence that Planet Nine might not need to exist, after all. Ann-Marie Madigan, who leads the group, presented the group’s findings at last week’s American Astronomical Society meeting, which ran from June 3-7, 2018 in Denver. Her team’s statement said:

Bumper car-like interactions at the edges of our solar system — and not a mysterious ninth planet — may explain the the dynamics of strange bodies called “detached objects” …

In the new study, Madigan and colleagues Jacob Fleisig and Alexander Zderic, also of CU Boulder, looked carefully at the orbits of some of these objects. For example, they looked at the small outer solar system body 90377 Sedna, which orbits our sun at a distance of nearly 8 billion miles (13 billion km). The orbits of Sedna and a handful of other bodies at that distance look separated – or detached – from the rest of the solar system. These strange orbits are what led Caltech astronomers Mike Brown and Konstanin Batygin to propose a Planet Nine in the first place.

Brown and Batygin had suggested that an as-yet-unseen ninth planet – four times the size of Earth and 10 times Earth’s mass – may be lurking beyond Neptune. They suggested the unknown planet’s gravity was influencing the orbits of the “detached objects.” Since 2016, astronomers around the world have been searching for Planet Nine, but no one has found it yet.

Meanwhile, Madigan, Fleisig and Zderic have explored a new idea about the orbits of these outer solar system bodies. The new calculations show the orbits might be the result of these bodies jostling against each other and debris in that part of space. In that case, no Planet Nine would be needed. Madigan said:

There are so many of these bodies out there. What does their collective gravity do? We can solve a lot of these problems by just taking into account that question.

Ann-Marie Madigan, Jacob Fleisig and Alexander Zderic of the Eccentric Dynamics group at CU Boulder. Image via CU Boulder.

Madigan pointed out that the outer solar system is:

… an unusual place, gravitationally speaking.

Once you get further away from Neptune, things don’t make any sense, which is really exciting.

Her team’s statement explained:

Among the things that don’t make sense: Sedna. This minor planet takes more than 11,000 years to circumnavigate Earth’s sun and is a little smaller than Pluto … Sedna and other detached objects complete humongous, circle-shaped orbits that bring them nowhere close to big planets like Jupiter or Neptune. How they got out there on their own remains an ongoing mystery.

Madigan’s team didn’t originally intend to look for an alternate explanation for the orbits of detached bodies. Instead, Jacob Fleisig, an undergraduate studying astrophysics at CU Boulder, was engaged in developing computer simulations to explore the dynamics of orbits. Madigan said:

He came into my office one day and said, “I’m seeing some really cool stuff here.”

Fleisig had calculated that the orbits of icy objects beyond Neptune circle the sun like the hands of a clock. Some of those orbits, such as those belonging to asteroids, move like the minute hand, or relatively fast and in tandem. Others, the orbits of bigger objects like Sedna, move more slowly. They’re the hour hand. Eventually, those hands meet. Fleisig said:

You see a pileup of the orbits of smaller objects to one side of the sun. These orbits crash into the bigger body, and what happens is those interactions will change its orbit from an oval shape to a more circular shape.

In other words, Sedna’s orbit goes from normal to detached, entirely because of those small-scale interactions. The team’s findings also fall in line with recent observations. Research from 2012 noted that the bigger a detached object gets, the farther away its orbit becomes from the sun — exactly as Fleisig’s calculations show.

An artist’s rendering of Sedna, which looks reddish in color in telescope images. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech.

These astronomers say their findings may provide clues about another phenomenon: the extinction of the dinosaurs. As space debris interacts in the outer solar system, the orbits of these objects tighten and widen in a repeating cycle. This cycle could wind up shooting comets toward the inner solar system on a predictable timescale. Fleisig said:

While we’re not able to say that this pattern killed the dinosaurs, it’s tantalizing.

Madigan added that the orbit of Sedna is one more example of just how interesting the outer solar system has become. She said:

The picture we draw of the outer solar system in textbooks may have to change. There’s a lot more stuff out there than we once thought, which is really cool.

Astronomers Mike Brown and Konstanin Batygin (@KBatygin on Twitter), both of Caltech, proposed Planet Nine in 2016 and are still trying to investigate it. Image via Lance Hayashida/Caltech/NASA.

Bottom line: Astronomers at Caltech proposed a Planet Nine in 2016, and other astronomers around the world have been searching for it. Yet no one has spotted it. Meanwhile, there’s research suggesting we might not need a Planet Nine to explain the strange orbits of small bodies in the outer solar system.

MORE ARTICLES

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "No Planet Nine? Collective gravity might explain weird orbits at solar system's edge"

Post a Comment